Let’s set the scene. The year is 1963. Selma, Alabama, is humid and hot and sticky. When James Baldwin and his brother David arrive at the Selma airport to support a voter registration drive for Black voters. SNCC’s executive secretary, James Forman, is waiting for them with a few other SNCC activists like Prathia Hall.

As Baldwin described,

We got to Selma early Monday morning, about 1:30 a.m. Alabama time. And we had a talk. Jim gave me some idea of the town itself. The proportion of Negroes is something like fifty-eight per cent, which is, of course, the key to the whole battle. It’s a cotton town. And poor.

However, someone else was also there to see them land. Baldwin and the event had gained the notice of the FBI. As author James Campbell explains, the federal agency knew about the Baldwins’s plans and followed them throughout their time in Selma.

From subsequent litigation we would find out that the FBI’s file on James Baldwin contains 1,884 pages of documents, spanning from 1960 (and Selma, Alabama) until the early 1970s. Somewhat bizarrely, the FBI accumulated 276 pages on Richard Wright, 110 pages on Truman Capote, and just nine pages on Henry Miller. Baldwin’s file was unique.

Beyond his political activities, the bureau was also interested in Baldwin’s personal life. In 1963 an FBI supervisor reported that “‘Information has been developed by the Bureau that BALDWIN is a homosexual, and on a recent occasion made derogatory remarks in reference to the Bureau.'” The next year, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover chimed in, asking in a memo, “Isn’t Baldwin a well-known pervert?”

The FBI was notorious for surveillance of prominent LGBTQ civil rights activists like Bayard Rustin, Lorraine Hansberry, Pauli Murray, and Barbara Deming. Historian Jared Leighton points out, “Making accusations of homosexuality against activists in the movement, as well as deepening dissension over the alliance between Black Power and gay liberation groups, could effectively further the FBI’s goals.”

James Baldwin, then, was in effect a sort of two-for-one. He was black, he was gay, and the FBI hoped he could be exploited.

Making the FBI’s Records Public

The question, then, is how do we know all this?

In part the answer lies within the Freedom of Information Act itself. Subsection (a)(2) of the Freedom of Information Act requires that certain agency records must routinely be made "available for public inspection and copying.” This public inspection obligation applies to all federal agencies, it governs almost all records covered by subsection (a)(2) and in subsequent rulemaking has extended to the maintenance of electronic reading rooms.

Electronic reading rooms are as they sound. Agencies post to public facing web portals documents containing material of public interest released in response to prior FOIA requests.

In practice, it’s a little loose. Officially, the DOJ has said there are no bright line rules for when the requirements trigger. If the agency has records "likely to become the subject of subsequent requests,” then agencies should put them in the reading room. However, there’s no set number for when ‘likely’ becomes likely enough. Likewise, the requirement was designed to help the citizen find agency statements 'having precedential significance' when he becomes involved in 'a controversy with an agency.’ However, neither DOJ nor the appellate courts have defined exactly what significance is significance enough.

The same principles apply to James Baldwin. As a person of public interest and the subject of frequent FOIA requests (by historians, biographers, interested members of the public etc) there is all the reason to proactively disclose available documents. However, in the same way defining “likely” and “significance” has eluded a set definition for decades, the availability of Baldwin documents is uneven.

For example, the CIA has released very little about James Baldwin, even though it appears that Baldwin was subject to their foreign surveillance efforts. In the CIA’s reading room there is a single document (“James BALDWIN arrived at Istanbul, Turkey from Athens, Greece via Air France on 13 July 1969.”).

In comparison, the FBI’s is much more extensive. You can see part one here, which is roughly chronologically older documents. You can review part two here, which is roughly chronologically newer documents.

What the Documents Say

The documents by themselves deserve a lengthy newsletter, but I leave that in part to more nuanced thinkers. I am only a legal professional, and I can hardly contextualize the many odd’s and end’s that ended up in the FBI’s files; much less address the palimpsest that eventually got posted on the FBI’s Vault / FOIA Reading Room.

All that said, I want to draw readers’ attention to five small, interesting paragraphs.

First, the file reflects a serious preoccupation with Baldwin’s work on its own terms. i.e., reading it closely, and more or less nailing his work’s meaning. In the example below, FBI agents read Baldwin’s “MY DUNGEON SHOOK: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation.”

Also, calling Jesus a “sunbaked Hebrew” is objectively funny. Here is the full quote.

White Christians have also forgotten several elementary historical details. They have forgotten that the religion that is now identified with their virtue and their power—“God is on our side,” says Dr. Verwoerd—came out of a rocky piece of ground in what is now known as the Middle East before color was invented, and that in order for the Christian church to be established, Christ had to be put to death, by Rome, and that the real architect of the Christian church was not the disreputable, sunbaked Hebrew who gave it his name but the mercilessly fanatical and self-righteous St. Paul.

Second, a true literary and cultural cast of characters make an appearance — owing no doubt to Baldwin’s own national and international significance in America’s conversation on race. On one page is the FBI’s documentation of Bob Dylan’s (in)famous acceptance speech at the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee two weeks after JFK’s death. The ECLC had awarded its annual Tom Paine Award to Bob Dylan for his contribution to the civil rights movement, and Bob Dylan took the opportunity to sympathize with Lee Harvey Oswald.

Dylan’s remarks have not aged well.

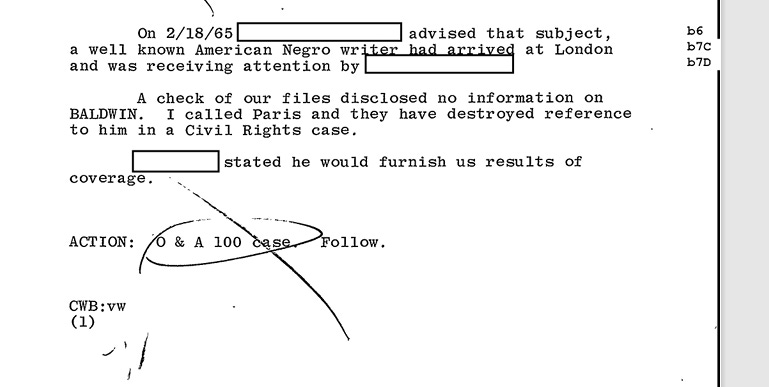

Third, I want to bring forward the notations on the right of the below document. It’s interesting to me that whoever the source is (the b(7)(D) reference) the mere mention of who they’re spying on (b(7)(C)) is embarrassing enough for the person being spied on that the FBI invokes protection for personal information in law enforcement records. I’ve reviewed a lot of FOIA documents, and while agencies are fairly maximalist with the notations their placement here is interesting given so many year later they’re still redacting the people Baldwin meets with.

Four, in 1963, the FBI added Baldwin to the Security Index, a “list of citizens who would be arrested first in the event of a state of emergency.”

Finally, a tidbit about Baldwin’s working habits.

If only my working habits were so punctual!

I am not the first one to observe that the Baldwin dossier does not resemble a work of nonfiction. The dossier scans for me as a type of postmodern novel, as fiction. I am so used to the dull, albeit accessible, rote paragraphs of federal bureaucracy I hardly know what to do with these documents. There are inclusions of media, and bizarre meandering observations like those quoted above. Characters appear, disappear and then are never explained. For me, I can hardly believe the document set existed as a set — but apparently it did as a huge, inscrutable redwall folder of clippings and excerpts.

And that, readers, is it. I hope you enjoyed reading.

This was an amazing article! The CIA surveillance of him on foreign soil. He spent lots of time in Istanbul and wrote Notes of a Native Son there. So glad I came across your Substack!

The line, "Baldwin does not say how," made me laugh. 😂

The format of this dossier actually looks very familiar to me. I think this is the format they use to compile dossiers on artists and public figures. I'm not sure if you know who Aaron Swartz was, but his FBI file is similar, as far as its contents, to Baldwin's, with media clippings, analyses of his social media profiles and blog posts, etc.