The FOIA Backlog in 2022

The more things change the more they stay the same

Background

One of my year-end activities is seeing what data federal agencies provide for their FOIA Programs. Under the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016 Congress tasked agencies with proactively making available the raw data used in the creation of the agencies’ final Annual FOIA Reports, the same reports that go to Congress.

I will take any excuse to play around with pivot tables and Excel. Given the two, at their intersection we have this post.

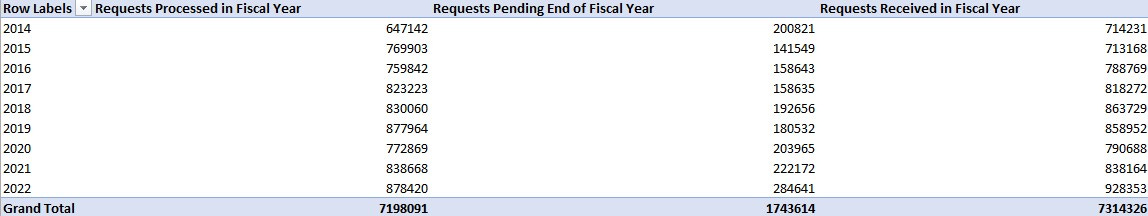

From my review, 2022 was a banner year for the Freedom of Information Act because ever more people were filing ever more requests. Nevertheless, the number of requests that are backlogged is far out of proportion to what the backlog was even four or five years ago.

2022 saw the biggest number of backlogged requests at 206,720 requests. For comparison, the lowest amount in the last decade was 2015 at 102,828 requests.

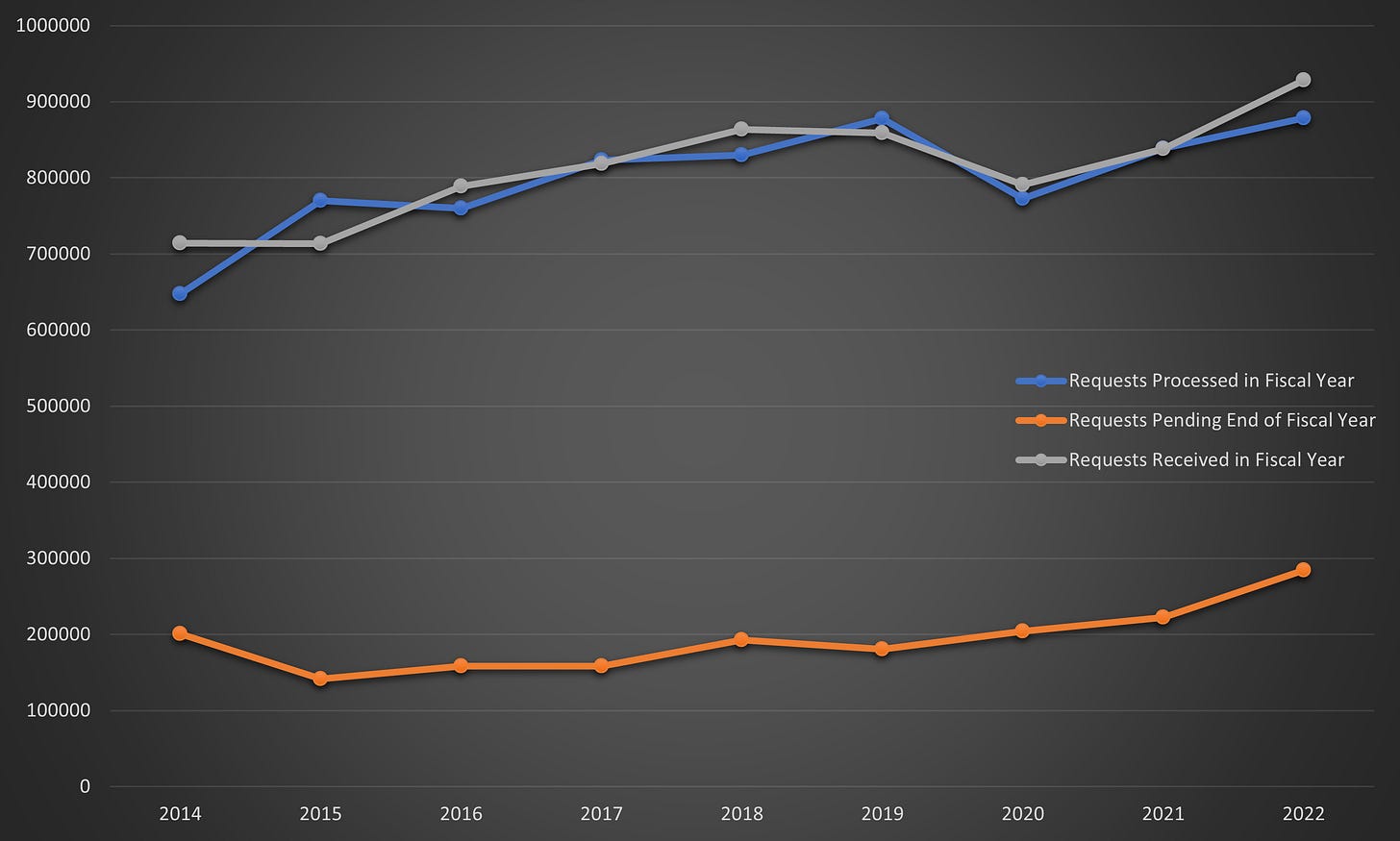

2022 saw the biggest number of processed requests at 878,420 requests. For comparison, the lowest amount in the last decade was 2012 at 665,924 requests.

2022 saw the biggest number of received requests at 928,353. For comparison, the lowest amount in the last decade was 2012 at 651,254.

This year did not happen in a vacuum.

As far back as 2007 federal agencies have been unable or unwilling to provide sufficient resources for addressing yearly FOIA Requests, much less making headway on the requests they were unable to process from the previous years. These unanswered requests, the FOIA “backlog,” is not necessarily defined the same exact way per agency. However, there are broad similarities, and the stats are good enough for rough comparisons.

After Congress took steps to address FOIA issues by enacting the OPEN Government Act of 2007 the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) has reported on the FOIA Backlog year in and year out.

To read GAO’s reports is to read the same thing reformulated in different ways.

The 18 selected agencies had backlogs of varying sizes, with 4 agencies having backlogs of 1,000 or more requests during fiscal years 2012 through 2016 [….] The 4 agencies with the largest backlogs attributed challenges in reducing their backlogs to factors such as increases in the number and complexity of FOIA requests. However, these agencies lacked plans that described how they intend to implement best practices to reduce backlogs. Until agencies develop such plans, they will likely continue to struggle to reduce backlogs to a manageable level.

From FY 2012 to 2018, the backlog of requests—that is, the number of requests or administrative appeals that are pending beyond FOIA's required time period for a response at the end of the FY—increased more than 80 percent.

FOIA request backlogs increased by 18 percent (from 120,436 to 141,762) from fiscal year 2019 to fiscal year 2020. Backlogged requests have been trending generally upwards since fiscal year 2016 (see fig. 8).41 From fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2020, backlogs increased by a total of 97 percent.

What the GAO reports should have said is that even if all agencies adopted all of the recommended “best practices” for FOIA processing, they would still face substantial backlogs of unanswered requests. The simple reason for that is that there is a mismatch between the growing demand from individual FOIA requesters and agency resources.

In order to bring the system into some rough alignment, it would be necessary either to increase the amount of agency funding appropriated and allocated for FOIA, or else to regulate the demand from requesters by imposing or increasing fees, limiting the number of requests from individual users, or some other restrictive measure.

But this post isn’t about commiserating with GAO.

2022 FOIA Backlog

Luckily for us all, FOIA.gov has enough robust data exporting for me to capture the latest saga with some Excel charts. I also uploaded the data here. A fair warning, it’s an .xls document and it’s not very pretty.

There is one rather large asterisk in the data and forthcoming charts, though how big not many people know.

The FOIA provides special protection for a narrow category of particularly sensitive law enforcement records. For these three specifically defined categories of records, Congress provided that federal law enforcement agencies "may treat the records as not subject to the requirements of [the FOIA]." 5 U.S.C. § 552(c). These provisions, which are referred to as "exclusions" provide protection in three limited sets of circumstances where publicly acknowledging even the existence of the records could cause harm to law enforcement or national security interests.

For example, the Department of Justice’s statistics are almost certainly underreported. Again, few people know precisely and those who know aren’t telling.

As I’ve been told a few times, numbers aren’t enough. People love graphs. I love graphs. So it goes.

Topline numbers are produced in the following graph.

As you can see, every year is another banner year for FOIA. What this means is that every year the agencies fall a little further behind.

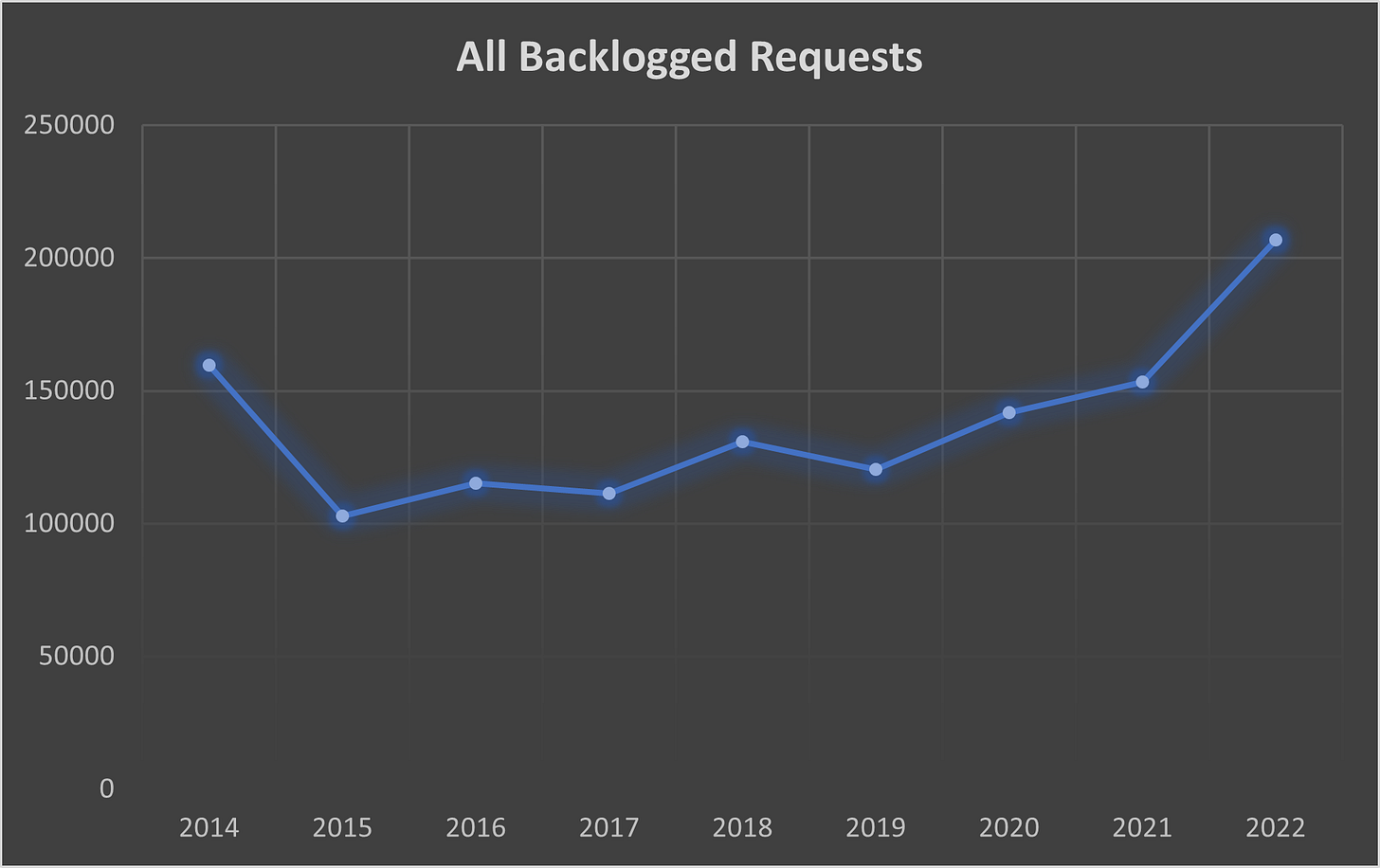

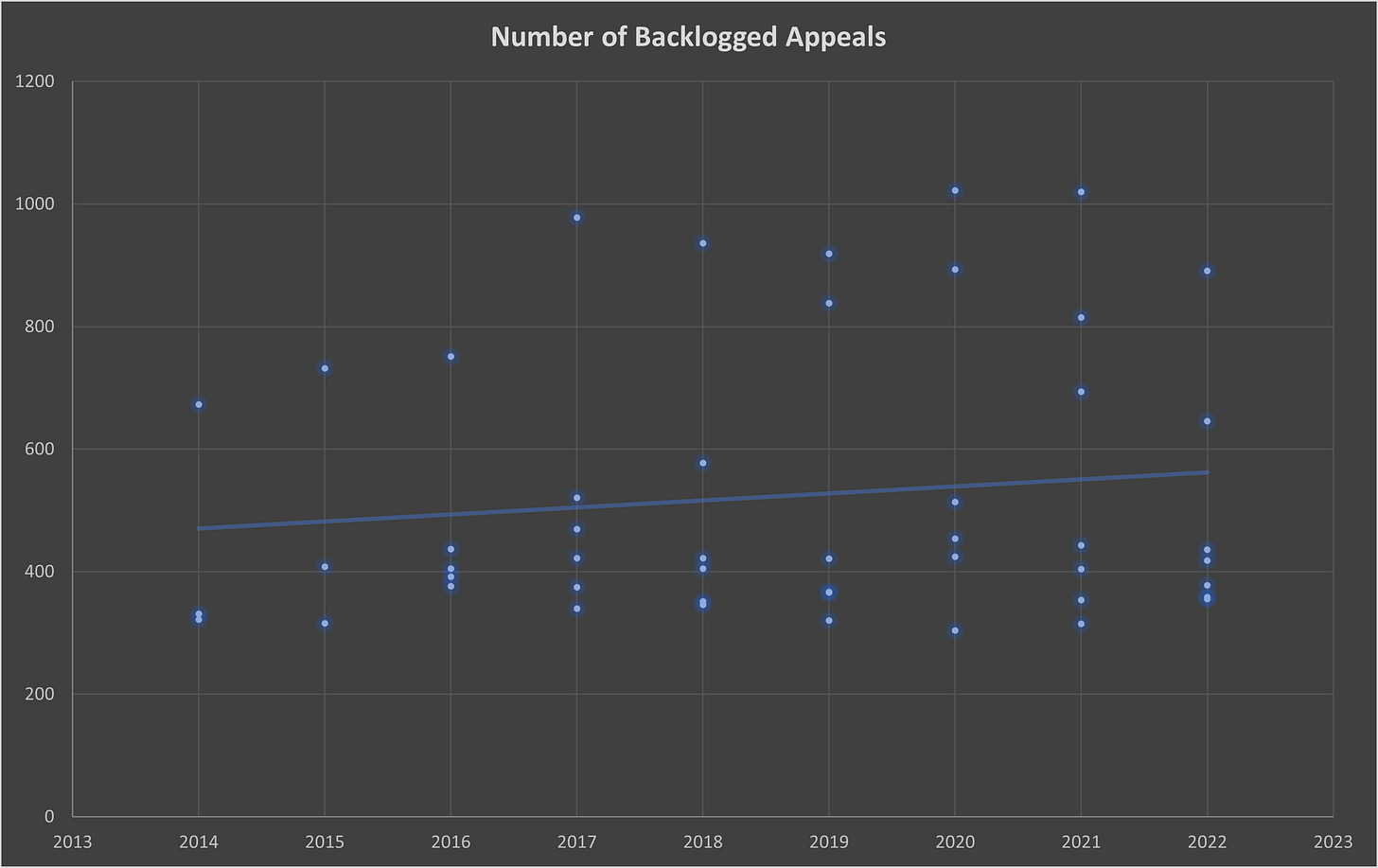

If there is any bright spot it is that backlogged appeals have gone down.

For context, administrative appeals are appeals to other parts of the same agency they are requesting records from. They are not “real appeals” to a real court. Some appeals are because a requestor was not satisfied with a component's initial response. Someone can also file an administrative appeal if they have requested expedited processing of a fee waiver and the component refused that request. Appeals must also happen to dispute a redaction or a withholding. In short, someone may appeal any adverse determination made by an agency and this number should be going down the fastest.

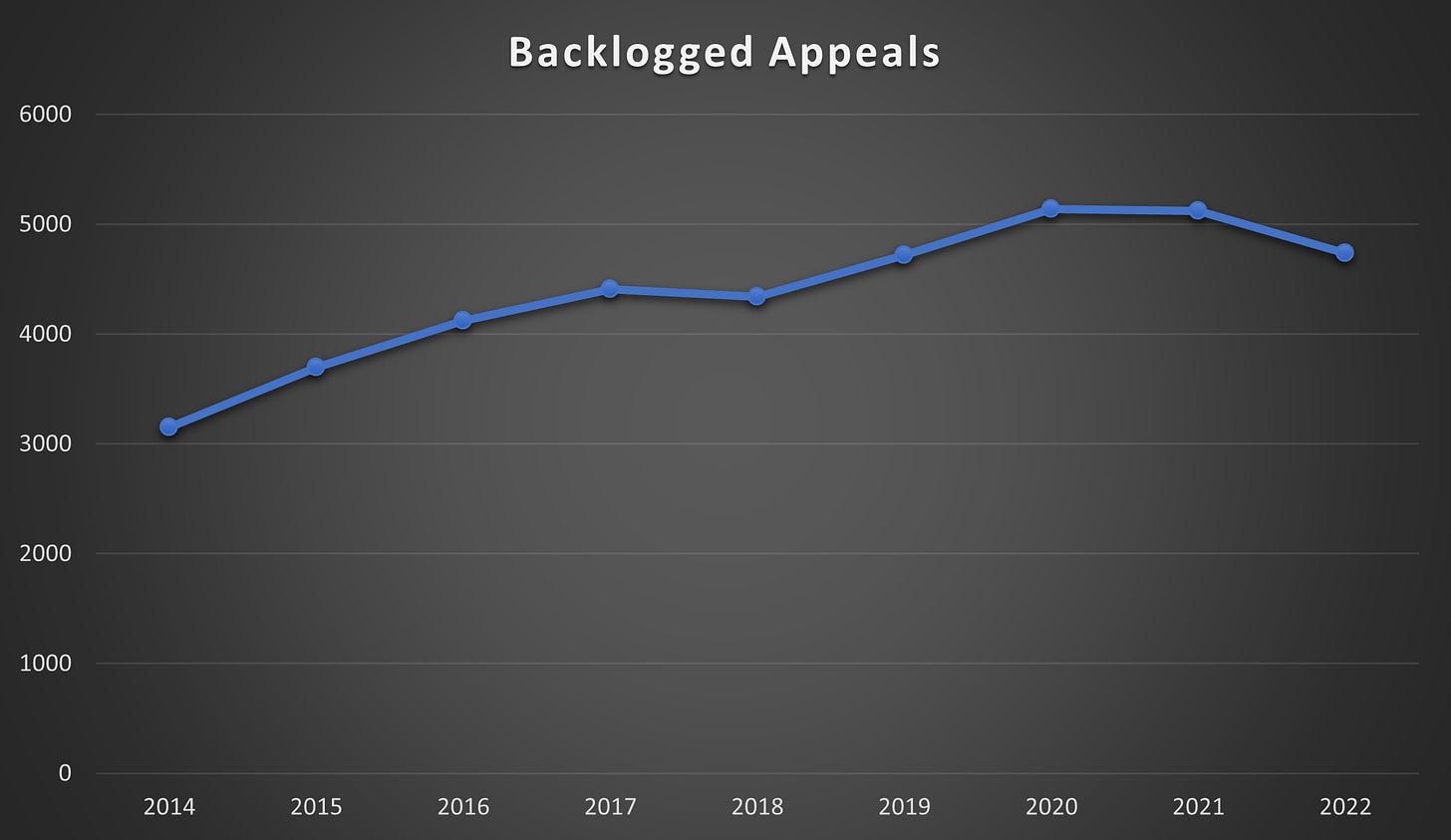

In another graph, I charted every time an appeal backlog got above 250. As you can tell, the dots and trend point to bigger backlogs and more of them over time.

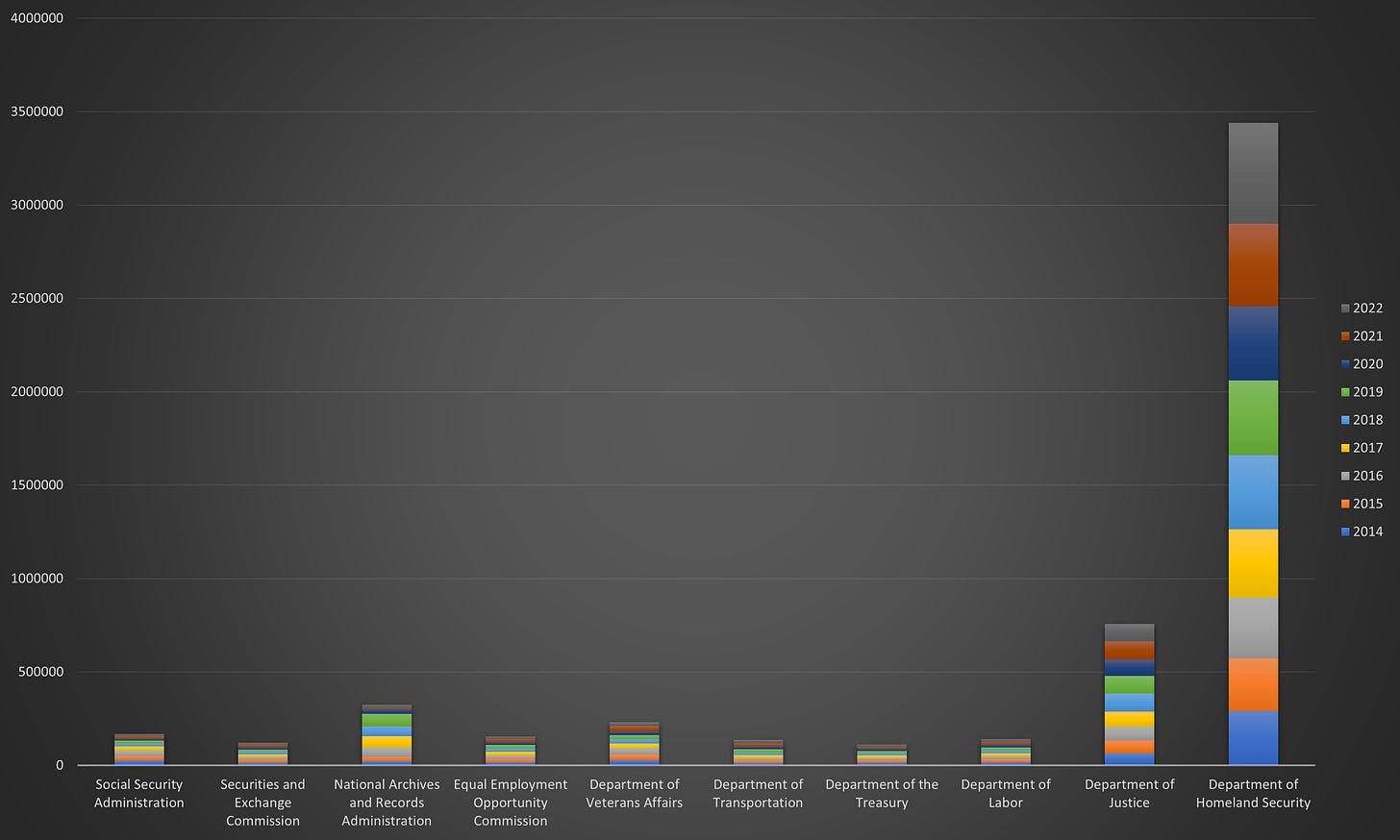

There is also data on every agency, which means there’s data on what agencies receive the most requests.

From 2014, the agencies that have had the highest average outstanding requests by the end of the year were:

Department of Homeland Security — 73759

Department of Justice — 25787

Department of Defense — 15844

U.S. Department of State — 14333

Department of Health and Human Services — 8606

National Archives and Records Administration — 5429

Department of Agriculture — 4750

Department of Transportation — 4495

Department of Veterans Affairs — 4234

Department of the Interior — 2731

This makes some sense given they were also the top ten most requested agencies on average. The big outlier is the Department of State, which received plenty but also still had plenty to go. This reflects their long outstanding backlog.

Department of Homeland Security — 382257

Department of Justice — 84116

Department of Defense — 55742

Department of Health and Human Services — 37314

National Archives and Records Administration — 35983

Department of Veterans Affairs — 25734

Department of Agriculture — 23685

Department of Transportation — 15048

U.S. Department of State — 14531

Department of the Interior — 6894

The data led me to creating this graph, which is a little too busy but it shows how consistently dominant the Department of Homeland Security is in terms of the overall FOIA burden.

What data would be very fun to have would be the ten oldest FOIA Requests currently outstanding at each of the respective agencies.

I recall years and years ago the National Security Archive, a project of the George Washington School of Law, “audited” FOIA Programs by asking that they produce the ten oldest FOIA Requests.

The oldest FOIA request unearthed by the Archive's Audit was submitted in March 1989 to the Department of Defense by a graduate student at the University of Southern California, asking for records on the U.S. "freedom of navigation" program. So much time has elapsed since the initial submission of that request that the requester, William Aceves, is now a tenured professor at California Western School of Law. Other agencies that have requests more than 15 years old include the Central Intelligence Agency, the U.S. Air Force, the National Archives and Records Administration, and the Department of Energy. The CIA claims four of the oldest ten pending FOIA requests in the government-from November 1989, May 1987 (Received at the CIA 1990), January 1991, and February 1991.

Maybe that’s a little side project for the future!

As I know nothing about FOIA this is an interesting series, thank you! I have a couple of 101 questions that were not answered by a quick Google search to provide context for the backlog. Does every request require human review and cross referencing that could potentially result in filing a reverse FOIA case or redacted information? Are most documents not digital and thus need to be retrieved manually from a filing system, copied and then mailed or held for pick up?

This is aggravating, and proof that a lot of legislation is passed for giggles and grins; apparently the Open Government Act did not and does not require each Agency to be adequately staffed or resourced, but it damn well should have: The simple reason for that is that there is a mismatch between the growing demand from individual FOIA requesters and agency resources.