I was delighted to discover that I am not alone in wondering what it looks like in federal agencies to respond to Freedom of Information Requests. I’m also not alone in filing FOIA requests about FOIA requests. At least once a year the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) files a lawsuit to understand how the government is living up to the promise of FOIA.

In their own words, AILA is a “nonpartisan, nonprofit, voluntary bar association that provides continuing legal education, professional services, information, and expertise to more than 16,000 attorneys who practice and teach immigration law.” They, like me, believe the nuts and bolts of how the agency trains its government information specialists speaks volumes about how transparency works.

The varied and entertaining history of AILA’s lawsuits is worth a post in its own right. For now, I want to direct attention to AILA’s latest request that ended up on their website in mid-January. AILA was gifted a large treasure trove of documents regarding how U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) responds to FOIA requests.

As immigrants’ rights advocates, we have all experienced the frustration of filing—and re-filing—Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests in order to obtain our clients’ files. The International Refugee Assistance Project decided to find out how USCIS and the State Department process our FOIA requests…by filing a FOIA.

To take a half-step back, among other responsibilities USCIS is responsible for adjudicating the applications of people seeking to be admitted to the United States as refugees. AILA’s members help individuals immigrate to the U.S. Regarding FOIA, which means specific documents, AILA members want the forms refugees submit to the USCIS designed to bring some order to the application chaos. USCIS also has internal guidelines for applications. USCIS also has a lot of random stuff, like fingerprints, and even proof that their clients’ homes were taken by Russia. These immigration attorneys are not filing lawsuits for these documents, they’re filing FOIA requests because immigration/deportation decisions are administrative actions.

Importantly, refugees / asylum seekers are interviewed by officers of USCIS’s Refugee, Asylum, and International Operations Directorate. And when a USCIS refugee officer reaches a decision on whether an applicant is eligible to be resettled in the United States, USCIS issues a notice to the applicant. USCIS also keeps a copy of the notice.

As you can imagine, good immigration attorneys often simplify their lives by getting their own copies via FOIA rather than using their clients as an intermediary.

The 225 documents about how USCIS processes FOIA requests is a long, interesting repository regarding training internal USCIS staffers. Repeating all of it at you, however, does not seem like a good use of your time or my time. Instead, I want to bring forward four quick things that I think deserve some mention (especially as we think about how other agencies are responding to my own meta-FOIA requests!).

No System Indexes

In 1996, when Congress passed the Electronic Freedom of Information Act (“E-FOIA”) amendments, they told each agency to index their major information systems. Congress’ reasoning was that if the agency never told anyone where records might be then the public likely wouldn’t ever get the records they want. The Infosystems Requirement was amended in 2016 specifying agencies must make the indexes “available for public inspection in an electronic format.”

Unsurprisingly, more than two decades after the E-FOIA amendments, agency uptake has been very uneven. USCIS does not have indexes or descriptions of their major information systems, and from my review of their documents they do not give their information specialists much guidance on how their own employees ought to go about making a justifiable search for potential indexes.

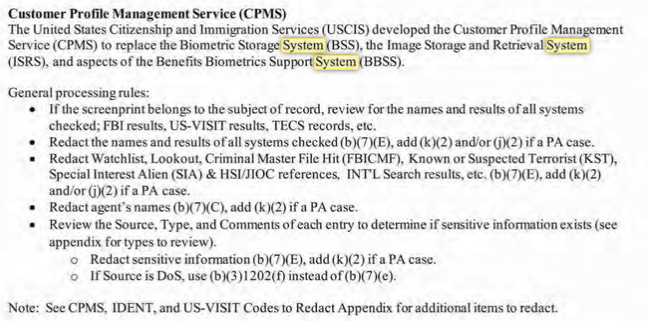

For example, in USCIS’ master “USCIS Case Processing Guide” starting on page 40ish the guide has system by system examples of what exemptions to look for in the specified systems.

But what seems absent is any defined way to know these systems might have responses information in them to begin with, and multiple systems referenced elsewhere are also absent.

AILA, for example, specifies in its own trainings to prompt the FOIA information specialists about the Alien Documentation, Identification and Telecommunications System; and the ENFORCE Removal Enforcement Module/Deportable Alien Control System. There’s a gap. I chalk this one up to ‘never attribute to malice what can be attributed to lack of resources.’

I also found additional training that highlights the gap. USCIS does not have an index of its systems, but USCIS also does not have a good index for its records either. For each system, there are multiple exceptions to USCIS’ main search parameter of A-Number.

To help explain, I’m calling on AILA’s expertise.

If there was ever a case of the blind leading the blind this might be it.

For example, let’s imagine a FOIA requests lists an USCIS A-Number. The FOIA request is from an immigration attorney. The FOIA request says it’s for this particular refugee, and the FOIA request has the relevant release of information waiver/form. If USCIS does not uniformly apply an A-Number to all immigration data, like refugee resettlement applications, there is a great temptation, then, for USCIS to insist the U.S. Department of State has the relevant records. Conceptually, the main immigration file might not have much beyond so-and-so applied to be resettled from [COUNTRY] at a U.S. Embassy.

Citizenship Determines Extent of Disclosure

I might have learned this, forgotten about it, and then relearned it; but the Privacy Act does not apply to foreign citizens.

Of further interest, the Department of Homeland Security has flip flopped its policy regarding the extension of Privacy Act protections. Apparently, during the Obama Administration, an Executive Order said noncitizens get the Privacy Act protections (and disclosure benefits). Then Trump reversed it.

As far as my research goes, I haven’t noted whether the Biden Administration reversed the reversal.

Either way, interesting to note that every request USCIS receives gets a flag for whether it’s about a noncitizen or a citizen. The flags are then proof that the information specialist at USCIS who is processing the request processed it.

Deleted Does Not Mean Destroyed

In the big bin called “why would they design it this way?” we can add USCIS’ internal electronic content management system for immigration petitions. There is a distinction within receipt files on whether USCIS has the documents or whether someone else does, such as the National Visa Center in the below example.

Yet within USCIS’ system there is apparently a toggle where one discovers whether the documents were destroyed in compliance with USCIS’ retention schedule or whether the documents don’t reside with USCIS. There is also no way to audit whether the notes are accurate or not, the answer is the processor offers up a lot of hopes and prayers that their predecessor had attention to detail when they were clearing out old records that no one needed anymore.

Litigation Cases Are A Mess

Finally, USCIS’ information governance is a mess when it comes to litigation cases. For a taste, here is a handy flowchart USCIS made for its information specialists.

For a little more insight, here is a specific “USCIS Lesson Plan for Court Documents.”

From my review, the pain point resides in the fact that when we are talking about USCIS there are both state and federal courts. There is also the Executive Office for Immigration Review and Board of Immigration Appeals.

USCIS, apparently out of desperation, throws all of it into one big pot.

I say out of desperation because when I think about governance for documents that have come out of one of immigration’s administration processes, if the same documents ever enter into state court or federal court then the redactions’ analysis likely changes. To go even further, if the documents are entered into a federal court as part of the appeal, like as an exhibit, and a final judgment is rendered, if they are requested after the end of federal litigation then the analysis changes again if requested.

In practice multiple attorneys must touch the exemptions. And yet, USCIS seemingly hopes that the information specialist is keeping it all straight without any formal review process. The entire step is bundled up as “Litigation Review.”

To take a real world example, Louise Trauma Ctr. v. United States Dep't of Homeland Sec., 1:20-cv-01128 (D. D.C. Apr 11, 2022).

Louise Trauma Center LLC sued about specific training (or lack thereof) for asylum officers.

I want to direct readers’ attention to this specific paragraph from the decision.

After the Court's ruling, USCIS provided the Center with reprocessed pages that were previously withheld under Exemption 5. See Joint Status Report at 1, ECF No. 46.

Whoops.

In other words, the documents departed from one of the FOIA processing doors while USCIS was simultaneously claiming in litigation that the disclosure would create a foreseeable harm.

Then, to compound the point, no one noticed other training slides had been previously disclosed and put out proactively by USCIS into the public domain.

Again, to go back to the flow chart, there was a litigation review that relied on the internal specialists to have this very broad, but simultaneously granular view of these specific documents while their own attorneys were making contradictory claims. Someone approved the trainings to go out, but then when it came time for a Joint Status Hearing in 2021, there was no mechanism to tell anyone that these documents were water under the bridge as far as disclosure went.

And that’s all for today!

I'll bet you wish you hadn't bothered to peek behind that curtain! Oh dear. Is it possible for human beings to make a system any more complex? It happens in so many areas of life that I am convinced that the objective is to make people just give up. Thank goodness people like you are keeping an eye on this and shining a light on it. Thank you.