Of the many things that keep me up at night (see, e.g., a 1000mg caffeine habit, staring at screens for hours, obsessing over social interactions from years ago) is that somewhere in Seattle one department is confidently answering a public disclosure request without any idea that an identical request has already been answered. In the nightmare the department is giving different documents. Sometimes less documents, sometimes more documents, but the number doesn’t matter. The core issue is governance doesn’t exist.

Data is difficult and expensive to decipher, manage, and control. The right technology strategy can turn that data into the source for better analytics and governance, but what happens in my corner of the world is that every data stream has its own strategy. Everyone is in the same boat but very few people are rowing in the same direction. Every month we are making progress, but it is what it is.

When requestors get different documents from identical requests the core purpose of public records laws is broken. People should expect consistency (and the right documents) from their government because to provide to one request one thing and the same request filed again another thing implicitly calls into question the government’s credibility. If the government can’t be relied upon to do the mission, then the government can’t be relied upon to be forthcoming about how the government runs.

Worse, the problem is not simple malfeasance. The problem is also not negligence. I say worse because malfeasance can be fixed, and negligence can be corrected. Unfortunately, public disclosure requests require time and attention. There are only so many resources to go around.

Call it schadenfreude, or maybe catharsis, but when I see other people have the same problems it lets me know that my professional obstacles aren’t unique to my organization.

With that all in mind, let’s look at two cases from the federal (FOIA) landscape that I believe highlight this common problem. In one we have the same request filed with two different agencies at the same time that produced two different sets of records. In other we have the same request filed at the same agency, but at two different times that produced two different sets of records.

General Mattis and the Washington Post’s Investigation

Case 1:21-cv-01025-APM

The Washington Post discovered that before he ran the Pentagon, General Mattis secretly worked for the UAE as a military adviser on the war in Yemen. The new documents were obtained by the Washington Post through a FOIA request and subsequent litigation.

The headline is exciting, but what I find even more interesting is the nuts and bolts of how the request was handled. Importantly, some departments (read: the Marines) all but failed at running a coherent search. If not for the State Department, the federal government would likely be on the hook for even more money than they already lost to Washington Post’s attorneys (more on that in a minute).

To take a step back for context, retired officers of the U.S. military hold an “office of profit or trust” within the scope of the Emoluments Clause because they “are subject to recall to active duty without their consent, and this obligation may be enforced by court martial under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.” See Applicability of 18 U.S.C. § 219 to Retired Foreign Service Officers, 11 Op. O.L.C. 67, 69 (1987). Congress has provided its consent to retired officers under the Emoluments Clause so long as the retired officers receive the approval of the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. 37 U.S.C. § 908(a)-(b).

At some point, the Washington Post, via the Project On Government Oversight’s FOIA request, were provided documents that showed a whole slew of former military officers had received approval to work in the Middle East.

POGO’s public-records request was for generals authorized to work for foreign governments. In the one directed towards the Marines, Mattis was one of seven retired generals. The heavily redacted spreadsheet revealed that he had applied to work as a military adviser to the UAE in 2015 but gave no other information. These retired officers also included Trump’s second White House Chief of Staff, John Kelly, President Obama’s first National Security Advisor, James L. Jones, and the 35th Commandant of the Marine Corps, James F. Amos.

In October 2020, the Washington Post filed FOIA requests with multiple branches of the armed miliary and their offices of inspector general. In response, however, the government made very broad claims about what material was exempted. Importantly, these exemptions applied to information concerning former Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

Thus, bringing us to the Washington Post article itself.

In the following document, General Mattis is asking the Marine Corps to approve his emolument from the UAE. Importantly, the document came from the State Department. The Marine Corps never provided Mattis’ letter.

The Washington Post journalist gave a reason why. The Marines “apparently lost this doc.”

Yikes, obviously.

But since you’re subscribed to this newsletter for more than me recapping a Washington Post article at you, I did take time to dig deeper into the affidavits filed by the people who have my job in the federal government.

In particular let's first compare the State Department’s affidavit explaining their search.

What a stroke of luck for the State Department. They receive the Washington Post’s FOIA Request, and it tracks what was already asked in other litigation. One stone two birds etc.

In comparison, the Marines’ search is a nightmare.

In response to the request to the U.S. Marine Corps, the Navy stepped in because the Marine Corps never really responded.

Then, the Navy identified 243 responsive pages and, on May 11, 2021, released 214 pages.

However, in response to the request that touched on the Marine Corps Office of Inspector General, the Navy stated that the office’s “files are not searchable by subject matter, only by the name of a subject or complainant or by the case number,” and that the Navy is, “therefore, unable to identify any records responsive to this request.”

Naturally, the Washington Post hated this.

The Marine Corps also had a problem of several cooks in the kitchen. Each request to the Marine Corps for approval to accept Foreign Government Employment is evaluated by judge advocates who draft a legal memorandum which accompanies the request through review and decision. These attorneys sit within the Judge Advocate Division (JAD) of HQMC, advising their principal, the Commandant of the Marine Corps as to whether it is legally advisable to support the applications for foreign government employment.

However, in the same breath the Marine Corps also has a component for retired officers in particular. The Separation and Retirement Branch of Manpower and Reserve Affairs at HQMC conducted a search of their paper files as well as an electronic drive on its network and, for their part, located 243 pages of responsive records.

The Marine Corps, recall above, also has an OIG’s office that sits next to all this making sure everything is being properly investigated.

In other words, you have this weird mix of the retired officers component, the judge advocates component, the actual commandant’s office(s), and finally the Marines’ OIG. No wonder the Marine Corps couldn’t find Mattis’ document. But, again, to be clear they were punished for it.

In sum, the search done by the Marines’ reads as a ‘how not to respond to FOIA requests’ because the issue is not simply denying or approving disclosures. The issue is there is no real central office, and there is no real coordination. Apparently, the Marines more or less assign the duty to collect records and transmit them to whoever is around. That’s one way to get yourself a hefty bill.

Young v. Mitsubishi Motors N. Am. Corp.

Case 2:19-cv-02070

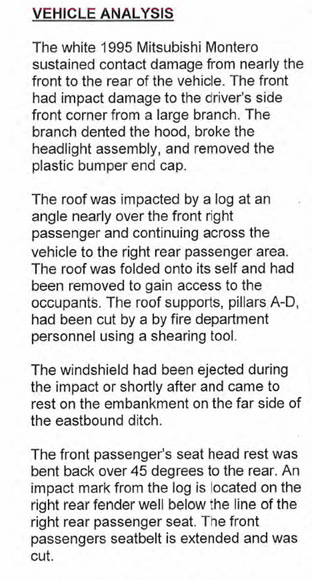

I am not going to give this subheader a clever intro because this lawsuit is based on a terrible event. Robert Young was driving a Mitsubishi through the Olympic National Park here in Washington when a diseased Douglas fir blew over and fell onto the roof of the vehicle, killing his wife, Julie Young, and minor grandchild, D.L.H., and paralyzing another minor grandchild, I.R.Y.

I am going to remove the gruesome photos and simply include a Washington State Patrol accident analysis.

Young hired an attorney and the attorney submitted two Freedom of Information Act requests to the National Parks Service.

The first request was submitted on March 22, 2017, and asked for “all materials within your possession or under your control relating to the investigation on January 1, 2017.” On May 16, 2017, NPS responded to the first FOIA request “with documents and correspondence regarding the event, investigation reports, photographs, and several emails.”

The second request was submitted on June 8, 2017, and asked for “Any Official Tree Hazard Program materials for Olympic National Park and any other official policy on tree maintenance, inspection, or removal.” NPS responded to the second FOIA request with a single document titled “Olympic National Park Hazard Tree Management Plan, May 1999.”

The attorney did some solo sleuthing of their own and in 2018 provided the records they had obtained through their investigation, including the records they had received from NPS, to an expert arborist. Based on an analysis of the available records, the expert opined that “any claim [against the federal government] would be barred under the discretionary function exception to the Federal Tort Claims Act.”

Defeated there, in 2019 plaintiffs filed again against Mitsubishi Motor Corporations and Mitsubishi Motors North America Corporations Inc. as defendants.

Naturally, Mitsubishi sent its own FOIA request to NPS and received “thousands of pages of documents” in return. The production included two key documents: (1) a May 10, 2017, letter from former forester Richard Cahill and (2) the 2015 Pacific West Region Directive: PW-062 Hazard Tree Management Plan.

Crucially, PW-062 “direct[s] NPS to identify and remove hazard trees alongside U.S. Highway 101 at Lake Crescent,” a directive that was not imposed by the 1999 Tree Hazard Plan that was previously produced to Young’s attorney (and arborist). A reasonable mind, knowing the Hazard Tree Plan, and reading the Cahill letter, could very easily arrive at the conclusion that the National Park Service failed to monitor hazard trees like the one that killed Young’s wife and minor child.

Since this case is still ongoing there can only be so much speculation, but crucially there appears to be a lack of record keeping at the National Park Service. In particular, the government has claimed it will show that one of the two withheld documents, the May 2017 Cahill letter, did not come into NPS’ possession until two days after the agency responded to the first FOIA request. However, the question of why the NPS didn’t make a subsequent search that ought to have discovered the letter is left unanswered… especially since the only document they did find seems to be simultaneously outdated and exonerating. Very coincidental!

And that’s that for today’s reading, I hope you enjoyed.

(I edited the newsletter several minutes after posting because of two or three unforgivable typos.)

As a rule I don't think organisations devote sufficient resources to FOI requests. It's seen as an add-on, and if records are not diligently kept it's really difficult to respond accurately and comprehensively. Great article again. I wish there was an equivalent Substack for the UK.

So the Government LIES and is FULL of SHIT?? Ight, Bet.