Background

I want my newsletter to educate, and what better way to educate than to talk about an exception to an exception to an exception?

Big picture, by statute, a government agency has twenty working days to determine — and to notify the requester — whether the agency will comply with a FOIA request. 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(A)(i). Many agencies have a stock letter that timely notifies requestors that they, the agency, have potentially responsive documents and where the agency believes the requested records are located. Perhaps the records are kept off-site, and, as a result, the agency cannot complete processing within twenty business days.

However, the twenty-day standard is not absolute. There are exceptions. One of them, "exceptional circumstances,” is the first layer of exception I referenced above.

Under FOIA, a government agency may obtain additional time to respond to FOIA requests if it "can show exceptional circumstances exist and that the agency is exercising due diligence in response to the request.” My emphasis. However, as an exception to that general exception, the FOIA statute further provides that "the term `exceptional circumstances' does not include a delay that results from a predictable agency workload." See 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(C)(ii).

To briefly recap, there is the general rule of twenty-days. As an exception, agencies can gain more time for “exceptional circumstances.” As an exception to the exception, “exceptional circumstances” cannot include “predictable agency workload.”

The exception to the exception to the exception is implied in the plain language of the statute’s use of “predictable.” “Exceptional circumstances” cannot include predictable workloads, but if the workload is unpredictable enough then agencies can get more time.

The question then is “who decides?”

Note well that the FOIA statute has “unusual circumstances.” “Exceptional circumstances” are an entirely different thing than “unusual circumstances.” “Unusual” is for when the agency determines administratively that the agency needs 10 more days to the 20 day timer. “Exceptional circumstances” is for when a court determines it. To answer the question “who decides,” a court.

Courts have interpreted the “predictable workload” provision to mean that exceptional circumstances exist, and a stay may be granted, when an agency is "deluged with a volume of requests for information vastly in excess of that anticipated by Congress, when the existing resources are inadequate to deal within the time limits of subsection 6(A), and when the agency can show that it `is exercising due diligence' in processing the requests." Open America v. Watergate Special Prosecution Force, 547 F.2d 605, 616 (D.C. Cir. 1976); see also Elec. Frontier Found. v. Dep't of Justice, 517 F. Supp. 2d 111, 116 (D.D.C. 2007).

One day we will have a post about Open America v. Watergate Special Prosecution Force, but not today. Briefly, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit heard a lawsuit over a FOIA request that was deep in the FBI's then-existing backlog. The FBI preliminary identified that Open America’s request encompassed more than 38,000 pages of responsive records. The D.C. Circuit held in Open America that given the public’s immense interest in Watergate, the circumstances amounted to "exceptional circumstances" and as long as the FBI acted with "due diligence" they were allowed the time reasonably necessary "to complete its review of the records." 547 F.2d at 616 (using 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(C)).

The case is famous enough that it’s now legal shorthand for this exception to an exception to an exception. When an agency asks for an "Open America" stay, or when a Court rules, the analysis focuses on the time necessary to allow a defendant agency a sufficient period of time in which to reach a FOIA request in its existing backlog and to process it in an orderly fashion. Simultaneously, the agency argues that the circumstances are beyond the normal, predictable workload.

Hypothetical

Enough theory, let’s do a hypothetical.

Let’s place you, dear reader, in the position of a division chief. You have a mix of people that report to you. Your portfolio includes managing FOIA requests, Privacy Act requests, and even a few archival duties under the National Records Act. In fact, let’s also throw in some coordination duties with the Presidential Records Act just to keep it interesting.

A district court on one side of the country instructs you to rapidly disclose hundreds of thousands of documents. In another district court on the other side of the country another judge is also contemplating issuing a very similar order. Is another federal court’s order, or orders, considered part of the agency’s “predictable” workload? On one hand, a judge ordering an agency to do their job is as predictable a result as can be imagined. On the other hand, reasonable minds might acknowledge that a sudden production of tens of thousands of documents, even if they’re to correct a prior error, is still unpredictable.

Naturally, the answer is “it depends.” To help us answer the question, let’s look at a case in ongoing litigation that is about the exact same issue.

Children Health Defense Fund v. Food and Drug Administration

(As a small disclaimer, I know that the topic has been the COVID vaccine two or three times now. There is simply a lot of FOIA litigation around the CDC and FDA. Next time I will try extra hard to find an interesting issue in a normal context that has nothing to do with vaccines.)

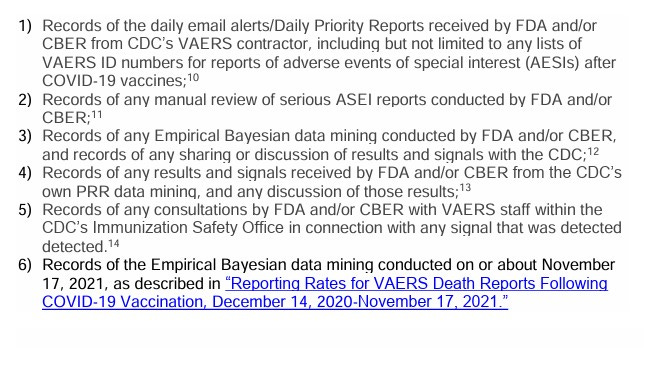

On January 16, 2023, Children’s Health Defense (the one founded by RFK Jr.) filed suit in an effort to compel the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to respond to its Freedom of Information Act request for “records connected with safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccines through the VAERS database.” Two screenshots are reproduced below: the letter’s coversheet and the page indicating the requested records.1 (This is the first time I am using Substack’s gallery function, so if it looks odd please tell me.)

In response, in November of last year the FDA moved to stay the case for eighteen months due to the “exceptional circumstances” presented by “another entity’s” FOIA request in the Northern District of Texas.2 A week or so ago of this year, we finally got the court’s decision on the FDA’s Open America motion after lengthy motions back and forth trying to convince the Court either to issue the stay or to deny it.

The entity referenced by the FDA should also ring a bell. The reference is identifying Public Health & Medical Professionals for Transparency’s litigation that I brought forward to the readers in the newsletter about unitization.

eDiscovery's "Unitization" Discourse and the Covid Vaccine

On January 3, 2023, the Freedom Coalition of Doctors for Choice submitted a FOIA request to the CDC seeking: All data obtained from v-safe users/registrants from the free text fields within the v-safe program for COVID-19 vaccines and the registrant code associated with each free text field/entry. (Note that all records from pre-populated fields, other t…

To briefly recap, the Texas federal court’s two orders required the production of approximately 5.7 million pages of COVID-19 vaccine-related records. The court orders in those cases require FDA to produce records to the FOIA requestors at an unprecedented rate: at least 90,000 to 110,000 pages per month from July 2023 to November 2023, and at least 180,000 pages per month from December 2023 to June 2025.

The reason the Texas federal court ruled as it did was because of the high public interest in the documents and, crucially, the district court simply didn’t credit that the document “pages” were actual pages. Instead, as I referenced, the district court viewed each disclosable unit as effectively a tweet. On a long page was a series of questions that were presumptively disclosable, and at the end there was a character limited box for other ailments that some people had filled in with personally identifiable information.

To answer the hypothetical, both sides broadly agreed on the relevant factors the court had to consider.

What I felt was particularly salient were two points, one for each side.

First, from Children’s Health Defense Fund,

Any challenge FDA faces in meeting its FOIA obligations is the result of its decision to assign the substantial work of processing vaccine-related FOIA requests to ALFOI without providing ALFOI sufficient staff to shoulder that load. But Open America does not allow an agency to punish CHD for the agency’s own decisions, particularly since the FDA has ample resources to staff its FOIA operations in a way that allows it to meet its transparency obligations under the FOIA.

Access Litigation and Freedom of Information Branch = “ALFOI.”

Second, from the FDA,

Since the PHMPT II order was issued in June 2023, FDA has produced between 90,000 and 110,000 pages per month in PHMPT I and PHMPT II, collectively; beginning next month, FDA must produce at least 180,000 pages per month in PHMPT II. See Mem. in Supp. of FDA Mot. (“FDA Mem.”), ECF No. 17-1 at 9; Burk Decl. ¶ 26, ECF No. 17-2.

Plaintiff does not dispute that the volume and rate of production ordered in PHMPT II is likely greater than any FOIA order in the history of this, or any, agency.

For the record, the Court did eventually side with the FDA.

The Court balanced that while the FDA’s workload re: the vaccine was predictable, the amount the Court in North Texas ordered was not. As the Court noted, the FDA went into the vaccine with the intention of proactively disclosing a large quantity of the at-issue data. However, the full “lifecycle” of the data meant that disclosing it now was not predictable.

Interestingly, both sides referenced a long string of cases where the FDA has filed similar Open America stays: Wright v. Dep’t of Health & Hum. Servs., Civ. A. No. 22-1378 (D.D.C.); Children’s Health Def. v. FDA, Civ. A. No. 23-2316 (D.D.C.); Informed Consent Action Network v. FDA, Civ. A. No. 23-0219 (D.D.C.); and Informed Consent Action Network v. FDA, Civ. A. No. 23-1508 (D.D.C.) (case voluntarily dismissed after FDA filed a motion to stay for eighteen months).

This is not the last time we’ll hear about the FDA.

Thanks for playing along, and I hope everyone has a great weekend.

Note, Children’s Health Defense Fund later added on with a second FOIA request in late 2022 that was also scooped up in the litigation.

Pub. Health & Med. Pros. For Transparency v. FDA, Civ. A. No. 21-1058 (N.D. Tex.) and Pub. Health & Med. Pros. For Transparency v. FDA, Civ. A. No. 22-0915 (N.D. Tex.)

fascinating. Were their more delays during the trump administration that those before and after? I can just see Rick Perry going "what nuclear documents? I thought we covered fossil fuels."